China’s growing appetite for discounted Russian oil has made it the leading financier of the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine by giving Moscow a reliable revenue source that blunts the impact of tough Western sanctions against its economy.

Four months after Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, China has overtaken Germany as the biggest single buyer of Russian energy, with oil sales to China — and India, another energy-hungry Asian nation — helping to fill a gap left by Europe, Russia’s largest export market.

China and India have together bought an estimated 2.4 million barrels of Russian crude oil a day in May, half of Russia’s total exports.

Despite being sold at a steep discount, the purchases — along with climbing oil prices — have allowed Russian revenues to grow in the face of Western pressure and given Moscow a crucial financial lifeline to keep funding its war effort.

Buying cheap Russian oil has allowed China to diversify its own reserves and given India a lucrative revenue stream by reexporting refined products like gasoline and diesel from the Russian crude. For the moment, the purchases don’t risk triggering secondary sanctions while the European Union’s current oil ban remains partial, but Beijing and New Delhi’s willingness to buy Russian oil will be put to the test later this year once stricter measures come into effect.

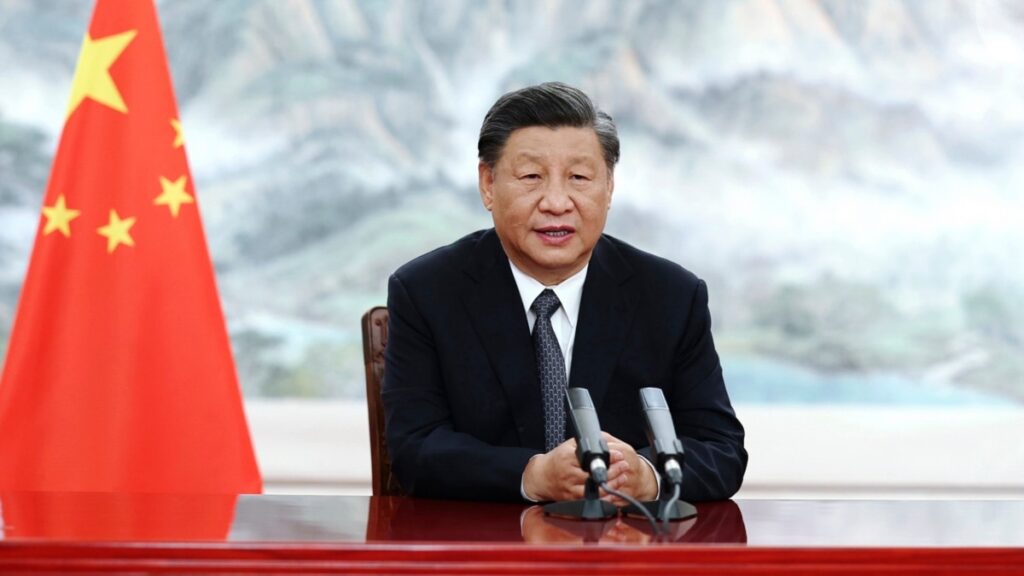

Meanwhile, Chinese President Xi Jinping hosted a virtual summit on June 22-23 for leaders of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, known collectively as BRICS, where he decried Western sanctions as “weaponizing” the global economy and called for the grouping to work closer together.

During his remarks at the summit, Russian President Vladimir said that BRICS countries were “developing Putin reliable alternative mechanisms for international settlements” and “exploring the possibility of creating an international reserve currency based on the basket of BRICS currencies.”

But how much can Moscow count on non-Western markets and partners, like China and India, to help it deal with the fallout of sanctions?

To find out more, RFE/RL spoke with Maria Shagina, a fellow at Britain’s International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS).

RFE/RL: Over the course of the war in Ukraine, China has now become the largest buyer of Russian oil. What does this mean for China and Russia’s relationship moving forward and is this a sign of their deepening partnership or Beijing simply making an opportunistic move to buy discounted energy?

Maria Shagina: We’ve heard on multiple occasions that Russia and China have established a “no-limits” partnership, and recently [on June 15]Xi reiterated support for mutual cooperation with Russia.

But we know that China’s rhetoric and deeds diverge quite a lot and that has been clear since 2014 [when Beijing and Moscow deepened their ties at a faster pace]. China is eager to capitalize on Russia’s isolation, including purchasing cheap Russian crude oil. But when it comes to violating Western sanctions, the Chinese private sector is usually quite.

In this case, we still don’t have [Western] sanctions on Russian oil and the oil embargo from the European Union will start on December 5. So there is still this phase-out period before sanctions are triggered, and this is the time for China — and also India — to capitalize on very cheap oil that they can purchase from Russia.

RFE/RL: Apart from buying oil, China has shown itself to be very cautious when it comes secondary to avoiding triggering sanctions imposed on Russia by the West. Should we expect Beijing to give more overt support to Russia in the future, especially when it comes to advanced technology like semiconductors?

Shagina: China’s balancing act is very delicate and, as the war progresses, it will be more difficult for Beijing to keep this position of so-called “pro-Russian neutrality,” where they’re officially neutral but lean toward Russia.

Since 2014, Russia has had rather high expectations of Beijing to step in to help out [with] this very difficult [financial] situation for Moscow. The Kremlin has since had a more sober assessment in terms of how much help can realistically be expected from China, but even now Russia is rather disappointed by the lack of support from China.

We know that there was some discontent from the Russian side when it came to the lack of Chinese support in terms of financial assistance and technology transfers after sanctions hit [following the February 24 invasion]. Those are the two areas that Russia is now highly dependent on China and other nonaligned countries for their support, and China will be one of the main countries to watch when it comes to helping alleviate the impact of sanctions. That’s not only whether Beijing will provide any financial assistance, but also whether it will provide any technology that is now under sanctions, like chips and semiconductors.

Lessons from 2014 tell us that the Chinese private sector is very risk-averse because it’s so dependent on the US dollar for transactions and tends to stay away from sanctioned Russian entities and even does overcompliance with sanctions to be extra careful. So in the current situation where we have an absolute number of sanctions in terms of their scope and their severity, I would say that there will be even more risk-averse behavior from the Chinese private sector.

But we should know that government-backed institutions behave differently. In 2014, Chinese banks like the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank worked with [Russian] companies like Novatek, which is Russia’s second-largest natural gas producer, to finance projects. So there is room to support sanctioned entities and people, but we should be cautious of the limited scope of this support.

RFE/RL: Xi Jinping hosted a BRICS summit and spoke about the grouping being important for the global economy, while Russian commentators have repeatedly said that the grouping is crucial for blunting Western sanctions. Does the war in Ukraine give an opportunity for it to finally deliver on its potential and play a more prominent role?

Shagina: I think that rhetorically there is a very strong narrative to push back against the West, in particular the United States and EU, over their use of unilateral sanctions that haven’t been supported by the UN.

India is another example [within BRICS] where Russia is also keen to expand collaboration, but we haven’t seen a lot of progress beyond buying oil. For example, Russia floated the idea to use different mechanisms for payment systems and alternatives to SWIFT, which it has been blocked from using under sanctions. But none of those initiatives has taken off and they remain largely dormant.

I think rhetorically the summit [was] an opportunity to resist US hegemony, but whether that will materialize into something bigger remains to be seen.

RFE/RL: Is there anything that you’re expecting to happen in regard to Chinese economic involvement with Russia that perhaps you think is coming or is worth watching out for?

Shagina: One area is semiconductors and technology transfers more broadly. This is something worth watching to see whether China will help. So far, as US officials have said, there has been no systematic support on the side of China, but whether China will be willing to supply them to alleviate this pressure from technology sanctions on Russia is not implausible given the level of partnership both countries have.

The other area that is worth watching is whether Chinese companies will help provide energy equipment that the EU ban on liquefied natural gas (LNG) and on LNG equipment has cut off and that Russia can’t substitute for on its own. Since 2014, Chinese engineering companies supplied up to 80 percent of this equipment, so there is room for China to step in to solidify its positions and potentially to provide additional financing for Chinese-backed [energy] projects in the Arctic.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

.