For a look behind the scenes of our data journalism, sign up to Off the Chartsour weekly newsletter

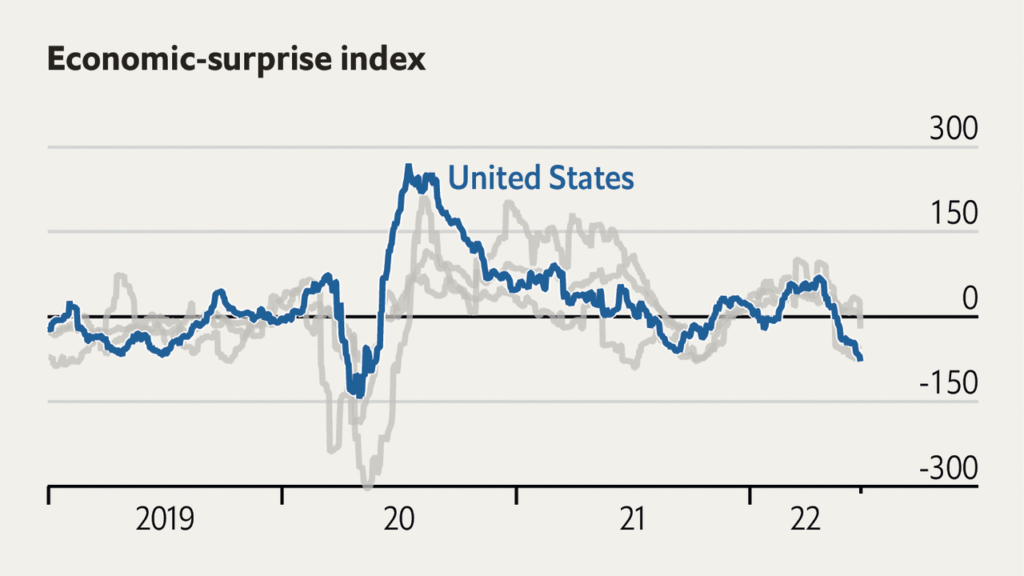

IT IS WELL known that markets hate uncertainty. Bad news, then, that by one measure the world economy is throwing up more nasty surprises for investors. Citigroup’s global economic-surprise index (CESI), which measures the degree to which macroeconomic data announcements beat or miss forecasts compiled by Bloomberg, has fallen into negative territory for the first time since November (the indices for America and China have been negative since mid -May). Since the summer of 2020 economic indicators had tended until recently to surprise on the upside. But as inflation has surged and consumer confidence has flagged, they are now failing to meet forecasters’ expectations. (See chart.)

Measures of economic surprises appear to be a useful way to gauge market sentiment. When the economy is booming data releases will typically be better than analysts expected, boosting the CESI. During an economic downturn, economic statistics will fall below the consensus estimate, leading to negative surprises. From June 2020 to July 2021, when the CESI for America was positive thanks to upbeat employment, inflation and housing figures, the S&P 500 index of big American firms rose by 38%. Since then the CESI has bounced above and below zero, and shares have fallen by roughly 9%.

In a paper published in 2016 Chiara Scotti, an economist at the Federal Reserve, constructed her own surprise index based on five indicators: GDP, industrial production, employment, retail sales and manufacturing output. America’s index also measured personal income. Ms Scotti found that positive economic surprises in America were associated with the appreciation of the dollar relative to the euro, pound sterling and yen. (In fact, Citi’s index was designed by the bank’s foreign-exchange unit for trading currencies, not stocks.)

But the surprise index can be hard to interpret. The CESI includes both backward- and forward-looking macroeconomic indicators, and is weighted in favor of newer releases and those that tend to have the biggest impact on markets. Because the index reflects economic performance relative to expectations, it can be negative during expansions if forecasters are too optimistic, and positive during contractions if they are too gloomy. But as Citi analysts wrote in a research note, “coincident rather than causal relationships are relied on even if they have no consistency whatsoever.” ■