There are financiers whose names adorn gallery wings and university dormitories. The world of money has even yielded a few who can be identified by first name only — at least to insiders. But there is only one that boasts their own hashtag.

Whenever Credit Suisse’s Zoltan Pozsar publishes research, the financial corners of Twitter will light up with comments on the latest from #Zoltan. (Even the WSJ has noticed the phenomenon.) Not everyone is a fan of his often complex explorations of the most recondite recesses of the financial system, or his far-ranging discussions on its future. But no one denies Pozsar’s influence, which is why FT Alphaville hit him up on a recent visit to New York.

Pozsar’s first brush with fame came in the wake of the financial crisis, when the young Hungarian economist became known as one of the leading taxonomists of “shadow banking”. But it is Pozsar’s recent ruminations on the future of the dollar-based global financial order in the wake of Russia invading Ukraine that have transformed him into one of Wall Street’s most read (and most controversial) analysts.

zoltan just called the end of bretton woods ii. that’s curtains as far as i’m concerned.

— nic soft landing carter (🌈 ) (@nic__carter) March 8, 2022

It has even catapulted Pozsar into an unusual measure of crossover fame for the finance industry. The historian Adam Tooze recently described Pozsar as the HG Wells or Jules Verne of what he called “financial fiction”, given his “conceptual depth” and “brilliant and intellectually fertile” writing on what the future of global finance might look like.

Pozsar admits he bridled at the insinuation that what he does is in any way fiction. But he brightens when I point out that the reason why Wells and Verne are still held in such high esteem today is not purely because of their literary merit, but because of their foresight in seeing what the future might hold. Too much research is “so goddamn dry,” he argues. “You have to tell a story.

“When you stick your neck out with a view you don’t know if it’s going to happen. But you kind of feel it’s going to happen, because you think logically it has to happen, and then you hopefully see it in the numbers. If you wait until the data shows it, it’s too late.”

Pozsar was born in 1978 in Pécs, southern Hungary, the son of two professors who taught mathematics and geology. That meant he grew up in a family with certain perks of influence and intellectualism. When the Iron Curtain fell his school suddenly switched from one history book to another — a comical way to mark the end of one regime and the dawn of another, but an event that shaped the young Hungarian profoundly. The end of communism also meant Pozsar was able to watch Beverly Hills 90210 on German satellite TV, giving a window into a very different world.

He admits to being a mediocre student aside from in the subjects that he really cared about. His big obsession was movies. Presaging his obsessive cataloguing of money markets, he collected and curated information on every film he saw.

“I was in the weeds,” Pozsar recalls. “I had a collection of about 500 VHS video tapes, and I had an Excel spreadsheet organised by genre, by director, by actors, by awards, how many times I watched it.”

This honed his language skills and helped him get into an English language programme at the University of Pécs, in spite of middling grades. It was there that he took his first economics class and studied the Asian financial crisis that had just erupted in 1997. “I got hooked,” Pozsar says. “I had no idea of what it all meant and how it fit together, but it was interesting. And then I became a very good student.”

Graduating top of his class meant that Pozsar was offered an eclectic assortment of scholarships. He first studied international economics at Sweden’s Jönköping International Business School, then briefly at the American University in Washington and finally at South Korea’s KDI School of Public Policy and Management where he took an MBA.

Aside from getting to see first-hand how South Korea had recovered from the financial crisis that had first triggered an interest in economics, Pozsar met the first of his big influences, the banker turned finance professor David Behling, who insisted that all his students took an accounting class.

“He taught it in a unique way,” Pozsar says. “He basically taught us to read balance sheets, income sheets and cash flows, and see how they all talk to each other.”

The Hungarian economist then started applying for jobs in the US. Banks were not hiring in the wake of the dotcom crash so he ended up working for Mark Zandi and his data company Economy.com, shortly before it was purchased by Moody’s.

It proved another formative experience, given Zandi’s prescient work on housing, household balance sheets and how they tied into the broader economy. “Influential people can all teach you simple things that cumulatively are very powerful,” Pozsar says.

It was at Economy.com that Pozsar wrote the first classically dense piece of #Zoltan research, on what would become his signature focus. It was the economist Paul McCulley who first coined the term “shadow banking” to describe the vast non-bank parts of the financial system that were seizing up at the time, but it was arguably Pozsar’s The Rise and Fall of the Shadow Banking System — and an accompanying “map” of what it looked like — that first helped solidify the concept.

Fishing for a new job, Pozsar sent his paper out to three people: the hedge fund managers Bill Ackman and John Paulsen, and Bill Dudley, who at the time ran the markets desk of the New York Federal Reserve. Dudley in particular was intrigued and hired the economist — just two weeks before Lehman collapsed.

Seeing the “amazingly effective” duo of Dudley and then-NY Fed head Tim Geithner work through the resulting financial maelstrom blew him away. “I was just a junior kid on the fringes of these meetings, but just watching these two people operate with such common sense, political sense and financial sense was extremely inspiring,” Pozsar says.

When things settled down, Pozsar suddenly found himself with a lot of free time on his hands again. So he spent a few weeks turning the little shadow banking map in his 2008 paper into an even more detailed three-by-four foot poster and pinned it up on the wall of the NY Fed’s briefing room to remind staffers that they spent too much time on what he reckoned constituted a tenth of the financial system. This in turn resulted in Shadow Banking, a paper that “put me on the map”, Pozsar says.

He then went to the IMF to work at a new group set up by chief economist Olivier Blanchard called Macrofinancial Linkages, then the US Treasury’s Office for Financial Research to cover the same issues and finally to Credit Suisse in early 2015, as an analyst covering the short-term interest rate markets. His boss James Sweeney wanted to see if all this wonky knowledge could be commercialised.

“It wasn’t really obvious what exactly I was going to do, but then I met with some clients — who had all read Shadow Banking — and it was very stimulating being exposed to traders all the time,” Pozsar says.

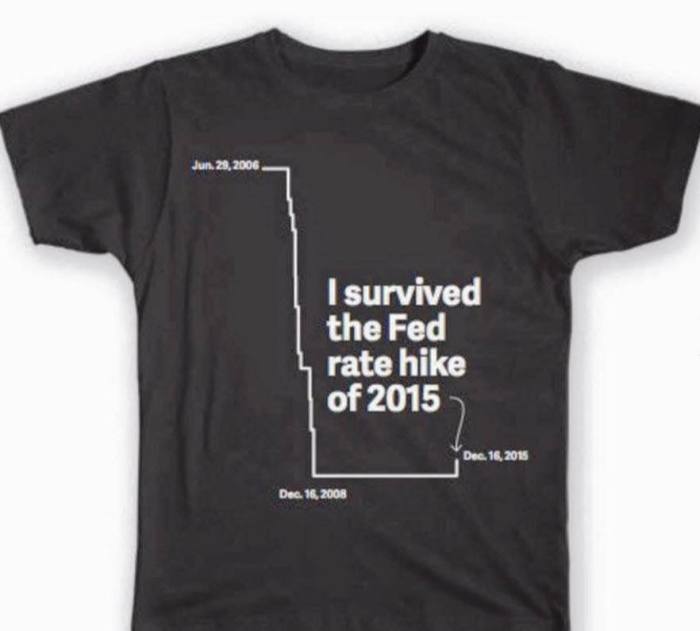

Pozsar joined Credit Suisse just as the Federal Reserve was beginning its painfully drawn-out process of raising interest rates for the first time since the financial crisis, so a lot of the Swiss bank’s clients asked him how he thought the Fed funds market would react. “I have no idea but I can look into it!” was Pozsar’s response.

He then began to dissect the weird ecosystem that surrounds the Fed funds market (the actual interest rate tool the US central bank uses to raise and lower the cost of money), mostly a motley group of state-sponsored US financial institutions known as Federal Home Loan Banks and the US branches of foreign banks in places like Taiwan and Scandinavia.

In this, he had help. The final, vital influence in Pozsar cobbling together the disparate, often obscure parts of the money markets was Perry Mehrling, an economics professor at Boston University. They first met in 2011 to discuss professor Mehrling book The New Lombard Street and Pozsar’s shadow banking work, and gradually grew close (Mehrling is now godfather to Pozsar’s daughter).

“He was an extremely important teacher. He basically gave me the framework,” Pozsar says. “I think of the shadow banking map as graffiti that I was basically just spraying on the wall: it looks cool but what the hell is this? Perry burnt into me that money is hierarchical. There’s a hierarchy of institutions, a hierarchy of prices, a hierarchy of spreads.”

Pozsar now sees himself as a mix of “Behling, Zandi, Merhling and McCulley in one big burger. I am what I am because of those four people,” he says. “Each and every one of them are different. They are not overlapping, they are additive.”

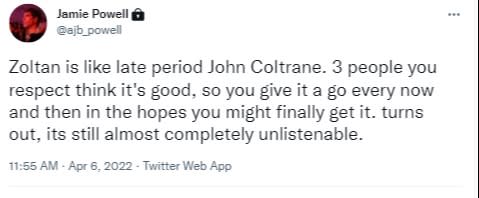

The result is research that even some geeky finance industry insiders complain is unforgivingly convoluted to read. For example, former Alphavillain Jamie Powell remained unconvinced (reposted with his permission).

But Pozsar argues that, sometimes, being difficult is unavoidable. “I recognise that some of this stuff is dense. But I think it’s also your duty to kind of educate the market about certain things,” he says. “If you read it all the time, you get used to the Zoltan language. And then you understand Zoltan . . . For example, I refuse to read anything with a regression in it, because I think that’s dense.”

Lately, Pozsar’s writing has gone waaaay beyond the core geeky money markets that he normally covers to more grandiose predictions for how the financial system as a whole is going to evolve — the opposite of the “dense” everyday #Zoltan fare.

His view is that the informal Bretton Wood II system — loosely defined as the modern era of reserve accumulation in the east being funnelled into western borrowing and consumption — has now run its course. The sanctioning of Russia highlighted how countries cannot necessarily always rely on access to these reserves, which means the “peaceful symbiosis” has been shattered, Pozsar argues.

His view is that the result will be a third Bretton Woods era, mostly defined by three main pillars: The Chinese renminbi is going to play a far larger, international role; gold is going to play a far bigger role in foreign currency reserves; and countries are going to stockpile reserves in essential natural resources in addition to financial ones.

“People are learning that you can have all the money in the world, but if you can’t buy shit with it, it’s a problem. So you might as well stock up on stuff,” Pozsar says. (For FTAV readers keener for a deeper view, Credit Suisse has published one of his signature pieces, to which Alex Turnbull has a good riposte.)

The reason why he has started to roam far beyond the tangled jungle of SOFR, Fed funds, FHLBs, cross-currency basis, GSIBs, SFR, repo rates, or IOR is his view that investment analysts need to be allowed some leeway to roam and adapt.

“If you focus on finance, every decade you have to focus on a completely new corner of the system to understand the risks and where things can get gummed up. I just find that fascinating,” he says. “The game always changes. If I was a money market strategist in the 1930s I’d focus on completely different things. I think the important thing is to adapt, and see how this thing we call ‘money’ matters from different perspectives at different times.”

Fundamentally, this is how he thinks investment bank strategists should approach their role. “You cannot be a mile wide and a mile deep. But you can be mile wide with a few mile-deep canyons. And the older you get the more canyons you can explore,” he says.

“But when you’re a strategist it’s very important to be able to catch the inflection points where things change. Maybe I’ve seen too many of these big moments in my life as a kid, but (when the west sanctioned Russia) I said, man, this is huge’”

As we stand up and stretch our legs, I ask him one final personal question. As someone else with a somewhat unusual name that was a burden in childhood but arguably an advantage in journalism, I cannot help but ask Pozsar whether he thinks at least some of his fame comes from having such a catchy, hashtag-friendly first name.

Pozsar laughs and admits he was glad his mother didn’t get her initial choice. “Thank god they didn’t call me Peter. But hopefully that’s not the only reason people read me.”

I missed Zoltan’s latest note, with this fabulous opening sentence. It is the sellside equivalent of the boxer who enters the ring to Tina Turner’s “simply the best” pic.twitter.com/DjdJV97YWD

— Dario Perkins (@darioperkins) April 6, 2022